A recent study led by researchers at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC) has resolved an old debate about the progenitor stars of the brightest planetary nebulae. The first author of this article, which has just been published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, is Rebeca Galera Rosillo, a doctoral student at the IAC who passed away in 2020 when she was finishing this work for her doctoral thesis.

The first and most important datum needed to grasp the nature of the universe is to know its size, to measure the distance to the galaxies. Just as in the Renaissance people began to work out the size of the Earth, and the positions of the seas and the continents, today we map the universe using distance scales which have been determined little by little, star by star, galaxy by galaxy.

Only a hundred years ago we did not even know that the galaxies are systems of stars, thousands of millions of them. It has been advances in technology, bigger and bigger telescopes, and more and more sensitive instruments, which have allowed us to study the galaxies and allowed us to start analizing their individual stars. Even today we cannot study ordinary stars such as the Sun in galaxies outside our own, but we can study them when they evolve, and in particular those that become planetary nebulae.

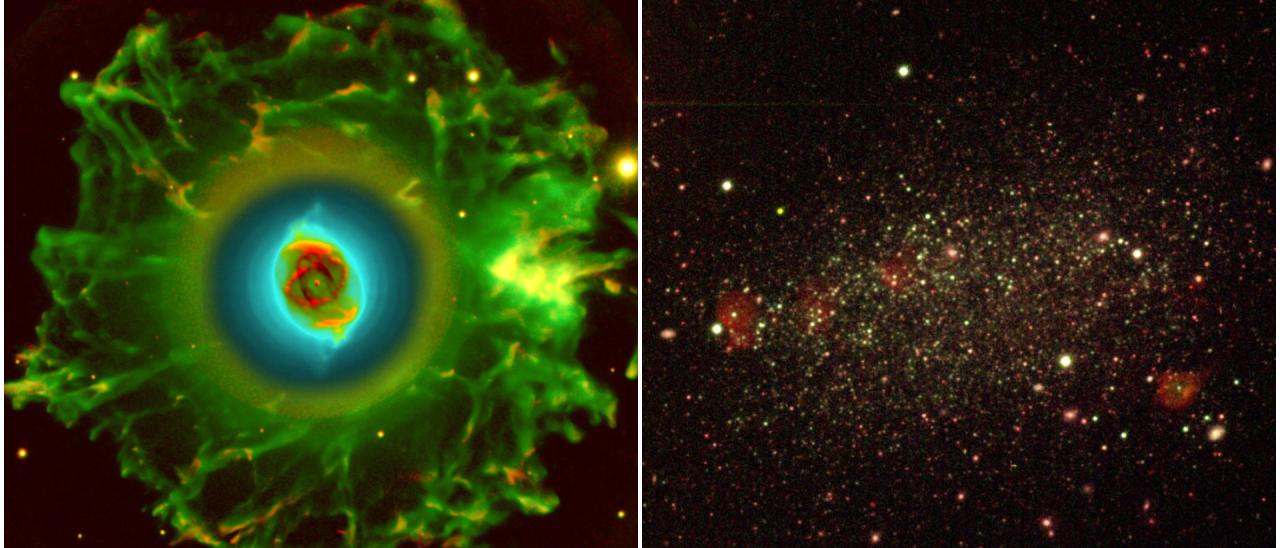

A planetary nebula is the gaseous envelope expelled from a star when it becomes a red giant, which is a critical phase in which the star cannot support the weight of its own mass, because it has burned all of its best and most abundant fuel, hydrogen, and it starts to use its reserve of helium. It is at that point when its internal nucleus becomes exposed, and because of its very high temperature (the surface of the star goes from some 3.000 Celsius to 100,000 Celsius or more in a few thousand years), it emits almost all of its light in the ultraviolet, heating violently the layers of gas which it has expelled, and ionizing them.

“What is fascinating is that these envelopes, which we call planetary nebulae, convert the huge quantity of ultraviolet energy of the star into visible light, and mostly into one emission line which is just where the human eye is most sensitive, in the yellow-green part of the spectrum” explains Antonio Mampaso, an IAC researcher and co-author of the article.” It is the emission line of doubly ionized atomic oxygen [OIII] 5007 Angstrom”.

According to Romano Corradi, the director of the Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC or Grantecan) and a co-author of the article, “the planetary nebulae are key to understand the chemical enrichment of the Universe, the ticking which marks the chemical advance towards the future. But it has also been shown that they can be used as rulers to measure the distances to the galaxies, because in all types of galaxies (spirals, ellpticals, young and old galaxies) all the brightest planetary nebulae have tthe same intrinsic brightness in their [OIII] 5007 Angstrom emission line, and they do not exceed this” This uniformity is such a robust property that it can be used to measure distances to galaxies at up to 70 million light years away, and even further. But the researchers do not know why the brightest planetary nebulae have luminosities which are all very close together, around a “magic” value of brightness, considering the variety of the physical processes involved.

Short lived but splendid

Standard theoretical models predict that the maximum brightness of a planetary nebula should be different according to the type of galaxy, and furthermore, that nebulae which are so bright should not exist in very evolved systems, because we expect that their progenitor stars are relatively massive, more than twice the mass of the Sun, which should have disappeared from the oldest systems. Observations contradict both of these assumptions.

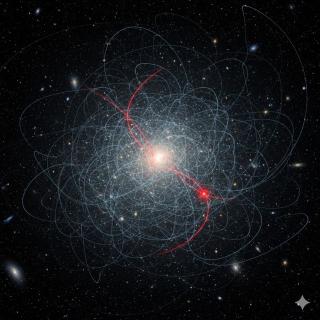

A team of eight astronomers, led by the IAC, and which include Jorge García Rojas, and David Jones, posdoctoral IAC researchers, has tackled this mystery, determining the physical and chemical parameters of the brightest planetary nebulae and their progenitor stars in the nearest spiral galaxy, the Andromeda galaxy, M31, with the highest possible accuracy. To do this they have obtained with the GTC, at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory, (Garafía, La Palma, Canary Islands) very deep spectra of a sample of planetary nebulae in M31. The result is that the brightest planetary nebulae are normal nebulae, with a density slightly above average, and with progenitor stars with masses close to 1.5 times the mass of the Sun.

“A recent piece of theoretical work, using the most advanced evolutionary models, suggests that stars with these masses could generate, at least during around a thousand years, planetaries as luminous as this” points out Mampaso. “The results obtained show that to undersand the brightest nebulae we don’t need massive stars, even though there are many of them in a galaxy such as M31.

This work was led by Rebeca Galera Rosillo, a doctoral student at the IAC who passed away in 2020 when she was finishing this research. She came from Puebla de Don Fabrique, in Granada. Rebeca was the only woman astronomer in the history of her village. After finishing her studies at the University of Granada, where she was an outstanding student, she joined the IAC in 2014 with a pre-doctoral contract for the training of research personnel under the supervisión of Antonio Mampaso and Roman Corradi. During her last years she worked as an astronomer at the Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes (ING) in La Palma, while finishing her doctoral thesis.

“Rebeca used to say that planetary nebulae are cosmic fireflies, they have short lives, shine brightly, and are beautiful”, remember her co-directors Corradi and Mampaso, “In her work as an astrophysicist she reached the frontier of knowledge, as far as one can reach today” they say, “But in addition to her passion for astronomy, she also left us her joy, and a visión of the world where music and art, solidarity with those who are suffering, and science, can be united to make the world better and more just.”

The Gran Telescopio Canarias and the Observatories of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC) are part of the Spanish network of Singular Scientific and Technical Infrastructures (ICTS).

Scientific article: Rebeca Galera Rosillo et al: “On the most luminous planetary nebulae of M 31”, A&A, Volume 657, January 2022, DOI: ttps://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202141890

Contact at the IAC:

Antonio Mampaso (IAC), amr [at] iac.es (amr[at]iac[dot]es)

Romano Corradi (GRANTECAN), romano.corradi [at] gtc.iac.es (romano[dot]corradi[at]gtc[dot]iac[dot]es)