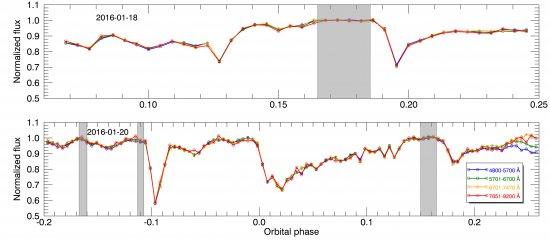

During the last decades, growing evidence about the presence of planetary material around white dwarfs has been established. The features of heavy elements in the spectra of a large fraction (25-50%) of these objects needs a frequent accretion of material orbiting close to the white dwarf. Additionally, at least 4% of these objects are known to host dusty disks. The space mission K2, that re-uses the Kepler instrument after a failure of two of its four gyroscopes, recently detected transiting material around WD1145+017, with periods in the 4.5-5h range, and a depth variability with scales of a few days. This is attributed to the presence of disintegrating planetesimals, due to the high temperatures close to the white dwarf. The K2 data suffer from a poor sampling to study this object (30 min), and they lack chromatic information. In this work, we used the IAC80 telescope to predict deep transits that were observed a few hours later with OSIRIS at GTC. The close to 1-min sampling, and the information in four visible bands, allowed for the first detection, with an unprecedented precision, of the color of the transiting material. The lack of depth changes in the different bands (gray transits) served to set constraints to the minimal particle sizes of the transiting material, which have to be 0.5 microns or larger for the most common minerals.

Two extracted GTC light curves in the wavelength ranges indicated at the legend, showing several eclipse events that have comparable depths in all the different colors.

Advertised on

References