In the image above obtained with the NASA’s spectrograph IRIS, can be seen in the bedge or limbo of the Sun the multitude of jets leaping the surface. In the center image, the numerical model is able to reproduce the jets. In the image below, taken with

At any given moment, as many as 10 million wild snakes of solar material leap from the sun’s surface. These are spicules, and despite their abundance, scientists didn’t understand how these jets of plasma form nor did they influence the heating of the outer layers of the sun's atmosphere or the solar wind. Now, for the first time, in a study partly funded by NASA, scientists have modeled spicule formation. For the first time, a scientific team has revealed their nature by combining simulations and images taken with the NASA’s IRIS spectrograph and the Swedish Solar Telescope of the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory (Garafía, La Palma). The study, led by Dr. Juan Martinez-Sykora, researcher at Lockheed Martin's Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory (California, USA) and astrophysicist at the University of La Laguna (ULL), is published today in the journal Science.

The observations were made with IRIS (NASA's Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph), a 20 cm ultraviolet space telescope with a spectrograph able to observe details of about 240 km, and the Swedish Solar Telescope, located at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory. This spacecraft and the ground-based telescope study the lower layers of the solar atmosphere, where the spicules form: chromosphere and the region of transition

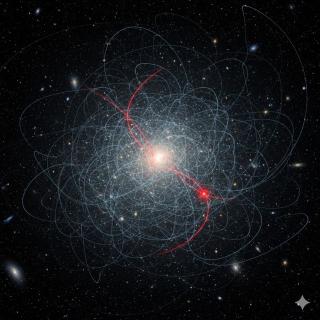

In addition to the images, they used computer simulations whose code was developed for almost a decade. "In our research," says Prof. Bart De Pontieu, also author of the study, "both go hand in hand. “We compare observations and models to figure out how well our models are performing, as well as how we should interpret our space-based observations.”

Their model is based in the dynamics of plasma — the hot gas of charged particles that streams along magnetic fields and constitutes the sun. Earlier versions of the model treated the interface region as a uniform, or completely charged, plasma, but the scientists knew something was missing because they never saw spicules in the simulations.

The model they generated is based on plasma dynamics, a very hot partially ionized gas flowing along the magnetic fields. Previous versions considered the lower atmosphere to be a uniform or fully charged plasma, but they suspected something was missing since they never detected spikes in the simulations.

The key, the scientists realized, was neutral particles. They were inspired by Earth’s own ionosphere, a region of the upper atmosphere where interactions between neutral and charged particles are responsible for numerous dynamic processes. In cooler regions of the sun, such as the interface region, plasma isn’t actually uniform. Some particles are still neutral, and neutral particles aren’t subject to magnetic fields like charged particles are. Scientists based previous models on a uniform plasma in order to simplify the problem — modeling is computationally expensive, and the final model took roughly a year to run with NASA’s supercomputing resources — but they realized neutral particles are a necessary piece of the puzzle.

“Usually magnetic fields are tightly coupled to charged particles,” said Juan Martínez-Sykora, lead author of the study and a solar physicist at Lockheed Martin. “With only charged particles in the model, the magnetic fields were stuck, and couldn’t rise to the surface. When we added neutrals, the magnetic fields could move more freely.”

Neutral particles facilitate the buoyancy the marled knots of magnetic energy need to rise through the boiling plasma and reach the surface. There, they snap producing spicules, releasing both plasma and energy. The simulations closely matched the observations; spicules occurred naturally and frequently.

"This result is a clear example of the breakthrough that can be achieved by combining powerful theoretical-numerical methods, state-of-the-art observations and supercomputing tools to better understand astrophysical phenomena", explains Prof.Fernando Moreno-Insertis, solar physicist at IAC, Professor ar the ULL and supervisor of the work Diploma of Advanced Studies (DEA) of Juan Martínez-Sykora. "The great complexity of many of the phenomena that occur in the solar atmosphere forces us to consider at the same time the dynamics of partially ionized gas, the magnetic field and the radiation-matter interaction in order to be able to explain them satisfactorily".

"This result is a clear example of the breakthroughs that can be achieved by combining powerful theoretical-numerical methods, state-of-the-art observations and supercomputing tools to better understand astrophysical phenomena", explains Fernando Moreno-Insertis, solar physicist at IAC, Professor at the ULL and supervisor of the DEA thesis (equivalent to a master´s thesis) of Juan Martínez-Sykora. "The great complexity of many of the phenomena that occur in the solar atmosphere forces us to consider at the same time the dynamics of partially ionized gas, the magnetic field and the radiation-matter interaction in order to be able to explain them satisfactorily".

The scientists’ updated model revealed something about solar energy transport as well. It turns out the energy in this whip-like process is high enough to generate Alfvén waves, a strong kind of wave scientists suspect is key to heating the sun’s atmosphere and propelling the solar wind, which constantly bathes the solar system with charged particles from the sun.

The National Academy of Sciences awarded Prof. Mats Carlsson and Prof. Viggo H. Hansteen, both developers of the model and authors of the study, with the 2017 Arctowski Medal in recognition of their contributions to the study of solar physics and the sun-Earth connection. Juan Martínez-Sykora included the effects produced by the presence of the neutral particles.

Article: “On the generation of solar spicules and Alfvenic waves”, by J. Martínez-Sykora et al. DOI: 10.1126/science.aah5412

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/356/6344/1269/tab-pdf

Contact:

Juan Martínez-Sykora: juanms [at] lmsal.com (juanms[at]lmsal[dot]com)