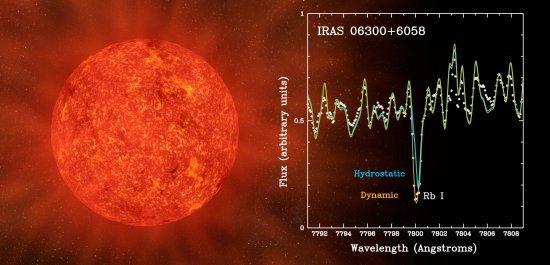

Intermediate mass stars, in their last phases of evolution ("AGB stars"),produce a large number of heavy elements (rich in neutrons), some ofthem radioactive isotopes, such as Rubidium and Technetium. Theseelements are pushed outwards to the surface of the star, and afterwards released into the interstellar medium. Among this type of stars, those least studied have been the more massive ones (between 4 and 8 times the mass of the Sun). Massive AGB stars have been recently identified in our Galaxy and in other nearby galaxies, such as the Magellanic Clouds, thanks to the detection of strong Rubidium overabundances in the spectra of these stars. However, the high abundances of Rubidium observed in these stars were a challenge for the theoretical models, which predicted considerably smaller Rubidium abundances. As apossible cause for this disagreement between theory and observations it was noted that the model atmospheres used previously to derive the chemical abundances were not sufficiently realistic for the AGB stars, because they did not take into account the large envelopes of gas and dust which surround the central star. In this work, we have determined for the first time the abundance of Rubidium taking into account the effect of the circumstellar envelope in a representative sample of massive AGB stars. We find that the Rubidium abundances determinedusing the new model atmospheres are much smaller, showing that our understanding of the nucleosynthesis in massive AGB stars is essentially valid. Given that the AGB stars account for the cosmic origin of more than 50% of all the elements in the Universe heavier than Iron, studying them has important consequences in other fields ofAstrophysics, such as stellar evolution, the chemical evolution of the galaxies, the origin of the globular clusters, or the chemical composition of the Solar System.

Figure caption: This is the spectrum of a massive AGB star (white dots) together with the predictions of the new model atmospheres (yellow line), and of the previous models which did not include the envelope (blue line). The Rubidium is detected as a very

Advertised on

References

Zamora et al. 2014, A&A, 564, L4